Top Gun

- 16 May 2016

- Thirty years after its release, this movie has proven to be both an effective recruiting tool and an enduring cultural icon.

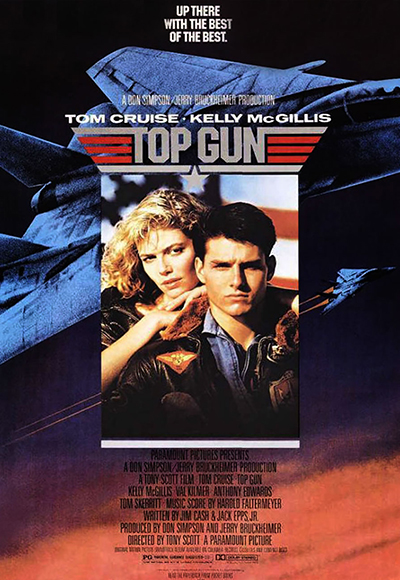

I’m barely old enough to remember the theatrical run of Top Gun, but I still have a mental snapshot of the poster of Tom Cruise and Kelly McGillis. Specifically, I saw it in a newspaper as a full-color, single-page ad. I didn’t know who they were, but I liked them. Tom Cruise was dark and handsome, and Kelly McGillis was blonde and beautiful. I never saw the movie in theaters or even at home, but I knew all about it.

I rented it this weekend to celebrate the 30th anniversary of its release. This highest-grossing movie of 1986 looks great in HD, and the aerial footage is second-to-none because it’s real. Some of the acting, singing, and writing is embarrassing, though. For better or worse, Top Gun is the quintessential 80s movie: there’s Soviet-backed adversaries, synthesizer-heavy music, and shoulder-padded blazers. It’s dated and cool.

The movie has lasting appeal because it features fighter jets, which have an air of chivalry and glamor. Tom Cruise’s Maverick is the hero whom everyone wants to be, Val Kilmer’s Iceman is the foil who is equally memorable, and Kelly McGillis’s Charlie is the damsel who represents the ideal of a modern woman. Top Gun has friendship and love as well as rivalry and war. It also has not one, but two, iconic songs written by Giorgio Moroder.

On one hand, the movie’s happy and hopeful jingoism is archaic today; Tom Cruise’s grim follow-up, Born on the Fourth of July, is like his recompense. On the other hand, renewed interest in the movie—and a possible sequel—wouldn’t be strong if it weren’t enjoyable to (re)watch. Younger Millennials might only know about Top Gun because of a running gag on Archer, but even the Library of Congress recognizes the need for speed.