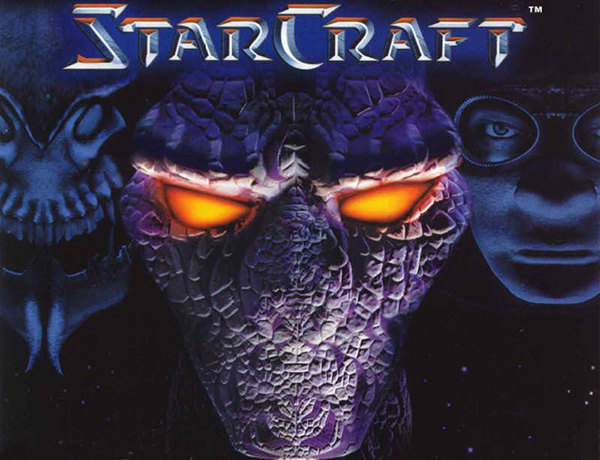

StarCraft

- 1 Apr 2018

- This computer game is probably the most important one of the past 20 years.

If GoldenEye 007 is my all-time favorite video game, then StarCraft is my all-time favorite computer game. Both are from the late 1990s, which is an amazingly memorable time for video games. StarCraft was released for the Windows platform on 1 April 1998 and forever changed the real-time strategy (RTS) genre like GoldenEye forever changed the first-person shooter genre. The influence of these games is apparent today.

I remember a short preview in GamePro that more or less described StarCraft as being WarCraft in space. I loved playing and completing the single-player campaigns of the

human-led faction in WarCraft II and its expansion, Tides of Darkness. (I never managed to finish the human campaign in the original WarCraft.) So, I wasn’t bothered by the idea of Blizzard’s next RTS game being a clone of their previous RTS game.

StarCraft could be a sequel that’s set in a different part of the universe and thousands of years in the future. The developers probably started with the same formula, but they ultimately decided to create three playable factions that came to be the Terrans, the Zerg, and the Protoss. Whereas the orc-led and human-led factions in WarCraft were basically mirror images of each other, the StarCraft factions were unique in their own ways.

The Terrans are ragtag humans from a military-industrial complex; the Zerg are parasitic arthropods from a colonial hierarchy; and the Protoss are advanced humanoids from a tribal society. The StarCraft lore also involves the Xel’naga, a superior race that precedes the other three. These types of races and societies are archetypes in the sci-fi genre; they also exist in Starship Troopers, Halo, and Alien vs Predator, for example.

Nonetheless, their inclusion in StarCraft made it interesting to play and to study. Each race had different units and different ways to develop and support these units. They catered to play styles that were introduced in the campaign, which was presented in three episodes. Each race had an episode, and if played in sequential order, the episodes told a truly epic story that the The Brood War expansion continued in the same way.

Besides the usual pre-rendered cutscenes before and after some missions, StarCraft introduced scripted events that happened during missions. Most these events were just conversations, but they made the game more immersive. On the other hand, the developers also broke the proverbial fourth wall by having countless references to books, movies, and shows as well as other games and real history.

The Blizzard team put a lot of thought into the StarCraft universe. The instruction manual reveals the history of each race and how they’re interconnected. This information is presented like a short story and provides context for the game’s plot. Moreover, everything that’s available for development by the player, as well as the science and factions of each race, is described with imaginative detail. I’ve read the entire manual four or five times.

I spent countless more hours with the Campaign Editor. I experimented with the pre-built triggers for making scripted events; I thought that it was useful because I was planning to study computer science, and this scripting was a basic way to practice programming logic. I entertained the idea of being a game designer, so I liked being able to customize mission briefings and link maps to make campaigns.

I had several ideas that were inspired by Rainbow Six, Saving Private Ryan, and Starship Troopers. The only map that I published on Blizzard’s Battle.net service was essentially cockfighting with Zerg Ultralisks. I imported a .wav file of the Mortal Kombat theme song and made it play whenever two players were doing battle in the central ring. I was proud of my creation, even though I got mixed feedback from a handful of players.

I never enjoyed playing the regular multiplayer mode, partly because I was never good at it. StarCraft matches required building a force in a hurry and then sending that force to rush the opponent. I never bothered to master keyboard hotkeys and micromanagement schedules because I was really only interested in campaign and novelty maps. I only won matches if I was on a team with good players like a couple of my friends.

Still, I respect the developers for their work on the competitive aspect of the game. It wouldn’t have been popular without balance, and it wouldn’t have stayed popular without depth. The original StarCraft, along with South Koreans, is most responsible for the establishment of eSports. I don’t care for eSports and I don’t expect them to ever compete with traditional sports, but the NBA and MLS have new eSports leagues.

The WarCraft and StarCraft series seem to have fallen out of favor. I’ve only tried WarCraft III and StarCraft II, and these iterations are nearly 16 and 8 years old, respectively. The continuous increase in the popularity of console gaming has made computer gaming, especially computer-only gaming, less relevant in general. Until a few years ago, I haven’t had a decent gaming computer since 2003, but I would buy a World of StarCraft game.

Traditional RTS games are a fringe genre these days, but MOBA games, also known as “action RTS” games, are really popular. My understanding is that these games are less focused on resource-gathering and force-building and more focused on attacking and defending; players control one unit or a small group of units as they compete for one of two teams. The rise of this sub-genre began with a player-created StarCraft map.

I don’t know what would’ve happened to me if I had continued making maps, and I don’t know what will happen to the series if Blizzard returns to it. I do know that the original StarCraft has provided immeasurable entertainment and motivation to me before running its course. I also know that I have to buy the remastered version.