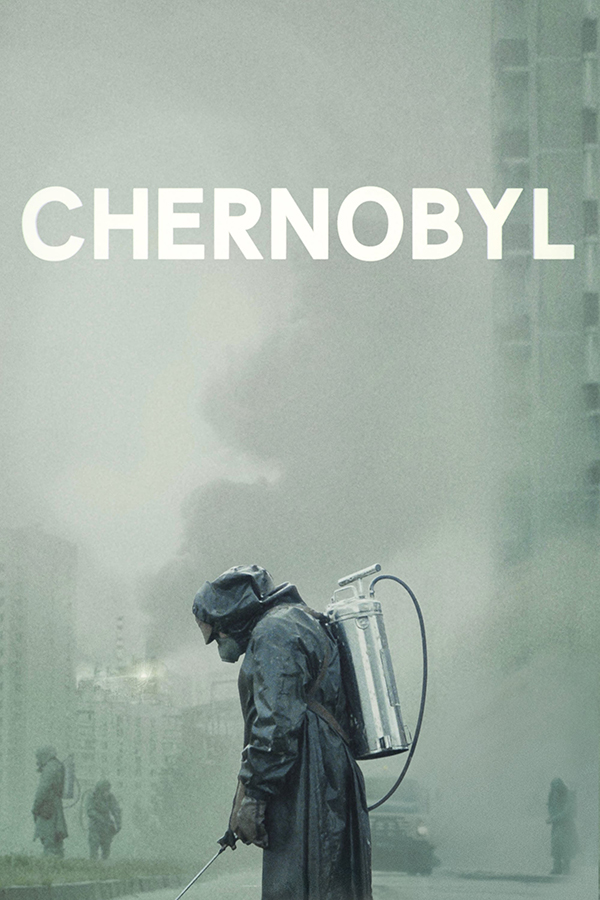

Chernobyl

- 15 Nov 2021

- This mini-series depicts events from 35 years ago, but the story is still interesting. It also serves as a warning that will always be relevant. The excellent acting and production will encourage more people to learn this history.

About a month ago, I finally watched the Chernobyl mini-series. It really was as gripping as I had expected. I finished watching the five hour-long episodes within a week. Some time during this period, I realized that the 35th anniversary was earlier this year. I’ve written about the nuclear disaster in the past, and its relevance hasn’t waned. Of course, the backdrop of the Cold War is one important reason for people’s enduring interest.

I recall Russian officials criticizing the series soon after its release. They’d promised (or threatened) to produce a series that would be, in their view, accurate. This response is noteworthy because the Soviet apparatus is the show’s underlying antagonist. The obvious antagonist is the tyrannical engineer who forces the fateful nuclear-reactor test. But the show reveals that the critical explosion has resulted from a state-redacted design flaw.

This design flaw is something that I hadn’t known until now. As one official says, ‘Our power is the perception of our power.’ The need to project this power is pervasive: using a Western-developed robot to clear debris is embarrassing to the state, and they place undercover agents and redacted documents in strategic places. They’re tropes, but they’re believable. The state’s grip is insecure, and it compensates with surveillance and secrecy.

Jared Harris and Stellan Skarsgard essentially play their most well-known character from other works. Harris is Valery Legasov, an otherwise-subservient technocrat who hangs himself like Lane Price in Mad Men. Skarsgard is Boris Shcherbina, a stern foil who becomes a steadfast ally like Gerald Lambeau in Good Will Hunting. Both leads are portraying real men though, and their unlikely bond is the core of this story.

Emily Watson is compelling as the third lead. She plays Ulana Khomyuk, a fictional composite who represents some of Legasov’s colleagues. The rest of the cast is good in their roles. The late Paul Ritter is the mentioned tyrant, Anatoly Diatlov. The only sub-plot that isn’t interesting is the new conscript in the exclusion zone. Everybody sounding like they’re from the British Isles is easy to overlook, after a while.

If the show is an indictment of the Soviet Union’s secrecy, it’s also a testament to its citizens. An English professor of mine once quoted an author who said that Russians were good at suffering. I forget the source, but Shcherbina alludes to this sentiment when he makes a speech to spur a group of locals for a foray that’s expected to be fatal. Three men eventually stand up, and even though they might not necessarily be Russian, they embody the embracing of hardship.

The most tense scene, by far, is the conscripts shovelling debris from the roof. Watching Chernobyl, and First Man, I’ve realized that I gravitate to historical drama. Nothing is as terrifying as things that have happened. There’s a dread that, no matter how extraordinary, they could happen again … and next time, they might not be surmountable next time.