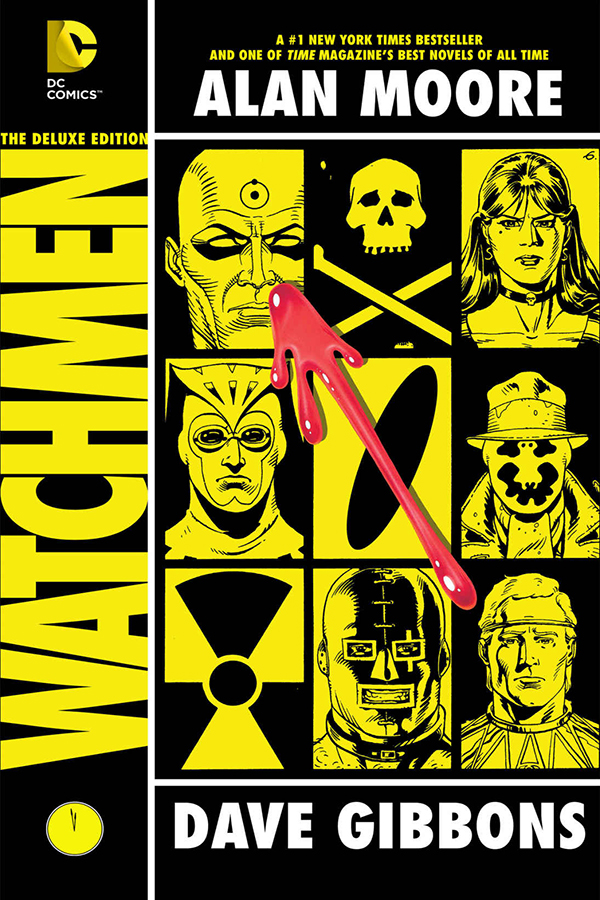

Watchmen

- 26 Dec 2017

- This comic-book series is at the pinnacle of its medium.

Then vs Now

I’ve long admired Alan Moore as a writer, and Watchmen is his most famous work. It proved that comic books could be a medium for deep stories, and for better or worse, it paved the way for grim and gritty antiheroes that followed its success. The series concluded its original publication schedule 30 years ago. Since October 1987, the world and the characters of Watchmen have been recognized and revisited again and again.

I bought The Deluxe Edition some time last year. I wanted to write about the book in 2016 to mark the 30th anniversary of the series introduction in September 1986. Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature at the end of last year, too, although he waited some months to accept the award. As Dave Gibbons wrote in the foreward, “It began with Bob Dylan.” Specifically, a couplet from Dylan’s “Desolation Row” inspired Gibbons and Moore.

Besides “Desolation Row,” lyrics from from “All Along the Watchtower” and “The Times They Are A-Changin’” are referenced in the book. The latter song is the soundtrack for the intro of Zack Snyder’s 2009 movie, which has three different versions; I’ve seen the theatrical release, and I own the Director’s Cut, but until recently I’ve forgotten about the Ultimate Cut, though I’ve seen the Tales of the Black Freighter animated short.

The Book vs The Movie

I can’t remember whether I’d read the book before seeing the movie or vice versa, but I would’ve done both during the movie hype. The book is better, not surprisingly. Its multiple-viewpoint approach, non-linear structure, and in-depth extras are interesting. The movie abandons or minimizes these things because of the limitations of its medium, but I’m focused on the fine details that are missing instead of the broad strokes that are preserved.

For example, Ozymandias ultimately tells Nite Owl and Rorschach how The Comedian had learned about his masterplan and why “the perfect fighting man” had surrendered to the inevitable (TDE 372-73). The Comedian foreshadows this revelation when he makes his drunken confession to Moloch (64). Simply put, the book answers questions about the premise that sets the story in motion, whereas the movie avoids these questions altogether.

Another example is Rorschach being intelligible in Ozymandias’s memory of the first Watchmen meeting (52). This flashback begs the question: is Rorschach’s way of speaking a choice, or a symptom? Even after his fateful case involving Blair Roche, the unmasked Rorschach shows sympathy for his landlady’s kids because their mother is a prostitute, like his late mother. The movie doesn’t have these instances of Rorschach being normal.

One thing that I prefer in the movie is the ending. Ozymandias blaming Dr Manhattan for the obliteration of New York, and the latter accepting the blame, is more plausible than everyone believing that an alien life-form has literally appeared out of nowhere. Nonetheless, Moore’s imaginative and thorough development of his world could only be fully communicated in print. A TV miniseries or video game might come close, though.

Art and Copy

The look and feel of Watchmen is easier to replicate than its tone and depth, but Gibbons deserve credit. Some of the panels look really cinematic and others are nicely understated; the bright palette, which favors sunset combinations, is a bold contrast to the dark story; and the designs of Dr Manhattan and Rorschach are as iconic as any top-shelf character in the DC library. I like Gibbons’s realistic, if somewhat bland, drawing style.

His work would be for nothing if Moore’s writing isn’t so meaty. Watchmen is on one level a mystery that starts with a murder and ends with near-Armageddon. On another level, the book is a deconstruction of traditional heroism in comic books and to some extent, policing and governance in general. On still another level, this opus is a collection of competing philosophies that naturally leads to debate about heady topics like agency and morality.

Fake History and Real Heroes

Watchmen follows an alternate course of history, but the real versions of key, fictionalized events still have public interest. The Doomsday Clock has actually existed since 1943, and this year, it’s been set to 11:57:30 PM, its second-most dire time, ever. In the past few months, historical records of the JFK assassination and the Vietnam War have made headlines, and even more recently, the Nixon administration has gotten the Spielberg-Hanks treatment.

This book is inspiring because the men who’ve crafted it are good. I don’t know if I can assume personas and assemble pieces as well as Moore or convey mood and create wonder as well as Gibbons, but I want to try. The Watchmen characters might not be worth emulating—which is partly why the book had been so ground-breaking for its time—but their creators are surely heroes.